Tuesday, April 4, 2017Hand Tracked Natural Interaction in VR

Virtual reality UX is hard. In the last year, our company has seen several virtual and augmented reality applications from inception to production. Each one has presented us with the same challenge; how to create an intuitive and natural user experience. Thankfully, every app brings us one step closer to answering this question.

Why is designing for virtual reality hard? I’ve asked a handful of developers and designers to come up with a list of common challenges when designing for VR.

1. Virtual reality is a new medium.

It has taken years to establish the best design practices for mobile apps. Even so, year after year, designers are continuing to refine and improve the definition of good user experience. Virtual reality is a new medium. There has not been sufficient time to discover the best practices.

Users are still learning how to interact with VR. Many users have not used virtual reality extensively. The more experienced users will tell you that every app has a different design pattern and controller scheme that needs to be learned. Users can’t just pickup a headset and go.

Deciding where to place interfaces is a difficult decision. Just about anyone who has designed a user interface for VR has asked the same questions: Where should I place this menu? Should this menu be in front of the user? To the side? How far should it be? How big should it be?

Complex interactions are not always easy to map to a controller. Every headset has a different input method: tap, gaze, point, Vive, Touch, hand tracking, dual stick controllers and the list goes on. Interactions that work well for one input may not work at all for another. More often than not, apps need to work with multiple control schemes.

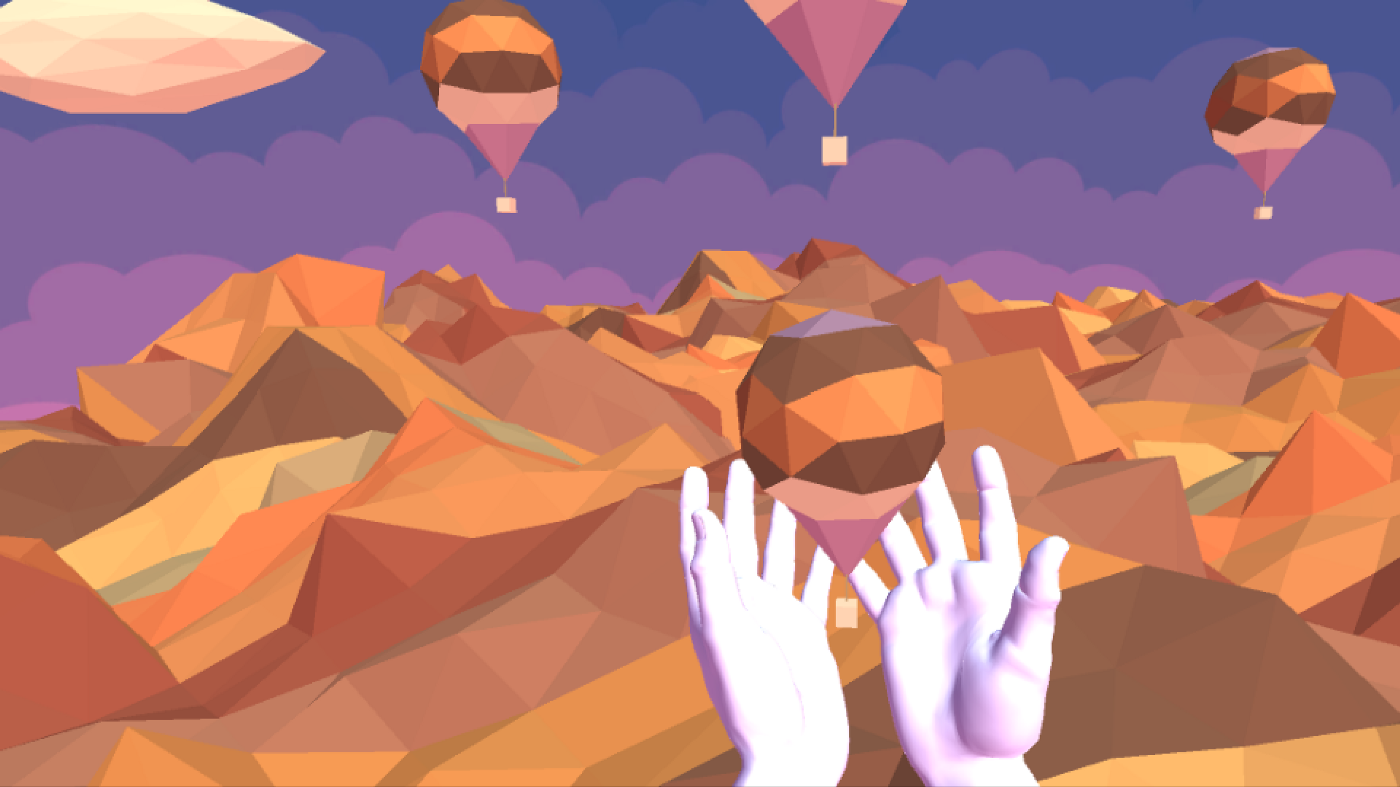

Six months ago we built an app for Colorado State University’s Office of the Vice President for Research. It provided an opportunity to go off the beaten path and try new ways of interaction. For the experience we integrated hand tracking using Leap Motion’s Interaction Engine. Quickly, it became apparent that designing for the hands enabled us to overcome these challenges naturally. There was a single user input mechanism, the user’s hands. Interface placement was simplified by placing items where we would in the real world. Users were able to pop on a headset and start using the app without any explanation.

"It became apparent that designing for the hands enabled us to overcome these challenges naturally."

Before our team had developed any experiences we would host demo nights to show off the coolest apps. The Lab by Valve was one our favorite to demo. Every time someone put on a headset, we would need to explain how to interact with the world. It required somebody hands on to walk users through every single step of the process. They would have to tell the user how to pick up items, teleport, open menus etc….

After completing the CSU app, it was time to demo. We had two of us run the demo on six headsets for over a hundred people in about an hour. Users were instructed to put on the headset, then reach out and press the button to start. We didn’t need to explain the controls or how to interact with the world anymore. All they needed to do was interact the way they have their entire life. Just reach out and touch.

Recently, the team built a Daydream app where users could interact with a 3D 360 filmed environment. Users interact with a menu to select a dress, once selected an actress would fade into view and model the wedding dress. Designing the user interaction presented us with the challenge of interface placement.

While there are still problems that are unsolved, these questions become easier to answer when designing for the hands (even if you aren’t using hand tracking). Distance is within arms reach. Size is what feels good when you grab it. Orientation is very much still hard, but designing for the hands allows you to solve the problem as you would in the real world.

The mouse is the primary way to interact with a computer because anybody can pick it up and start pointing. Touch has empowered us to interact with mobile devices because of how straight forward it is. Keyboards and controllers may enable power users for specific applications, but the vast majority of users don’t have the time or patience to learn controls. They just want to pick up and go.

Hand tracking enables users to complete complex tasks with simple interaction; the same way the mouse has empowered us to interact with computers without knowing the command line, or touch input has allowed us to throw away the Sidekick keyboard and d-pad.

Hand tracking is not without its faults. Most hand tracking is still beta quality — it works but has enough hiccups to be frustrating for extensive use. It has a low user adaption rate, people not only need to own the VR hardware but the hand tracking hardware as well. The hand tracking field of view is limited; you need your hands to be in the field of view of the tracker to interact with the world. Without haptics it there is some sense of disconnect between you and the virtual world.

Thankfully, this technology is evolving rapidly; an entire industry is racing to solve these problems. I wouldn’t recommend using hand tracking in most apps just yet, but I look forward to the day where I will. Designing for the hands has helped our team create natural, intuitive and powerful user experiences, and it might just help you too.